http://www.hss.adelaide.edu.au/philosophy/inconsistent-images/piranesi/

gods in love with mortals March 31, 2010

Both Lamia and Ode to Psyche are about gods falling in love with humans. Psyche was born a mortal and was made a god after Cupid fell in love with her, and Keats in turn would make his brain a temple to Psyche to “let in” the goddess’s “warm love.” The story of Lamia’s love for Lycius and that of Cupid’s for Psyche reach opposite conclusions: instead of the mortal Lycius getting elevated to immortality, both he and Lamia die. But, as I discuss below in terms of Keats’s consumerist religion, for Keats the line between death and immortality isn’t bright.  For instance it is precisely the deadness of the urn, its resistance to our attempts to attach living meaning and purpose to it, that makes it a vehicle of temporal transcendence. Likewise, I suggested that there is a sense in which, in The Eve of St. Agnes, the lovers’ bliss is simply incompatible with temporal life: when Porphyro and Madeline fall into each other’s dream they fall out of time. Hence the poem ends with a scene of very concrete mortal decay out of which the blissful lovers “glide” and “flee” like “phantoms.” For Keats immortality is always a phantom-dream projected from a context of time and mortality. Eve of St. Agnes and Lamia are both romance narratives – narratives of quests for love. Both narratives paradoxically suggest that love is both incompatible with and requires time: it is only from within a time-bound perspective that the dream of timelessness can appear as such. As Lamia particularly emphasizes, gods fall in love with mortals who strive to be god-like, which is what gods cannot do: there’s something wonderful about Lycius at the races appearing “like Jove” which Jove himself could never manifest. Time is the medium of narrative, a point which is especially underscored by the fact the Lycius appears god-like precisely while racing, as eminently human and temporal activity as there is. So although Lamia and the Eve of St. Agnes are romance narratives, insofar as they recount quests for unnarratable, timeless love, they are importantly also self-deconstructing narratives: they expose the formal incapacity of narrative to contain its own story. The love that would be narrated both presupposes and explodes the bounds of narrative time.

For instance it is precisely the deadness of the urn, its resistance to our attempts to attach living meaning and purpose to it, that makes it a vehicle of temporal transcendence. Likewise, I suggested that there is a sense in which, in The Eve of St. Agnes, the lovers’ bliss is simply incompatible with temporal life: when Porphyro and Madeline fall into each other’s dream they fall out of time. Hence the poem ends with a scene of very concrete mortal decay out of which the blissful lovers “glide” and “flee” like “phantoms.” For Keats immortality is always a phantom-dream projected from a context of time and mortality. Eve of St. Agnes and Lamia are both romance narratives – narratives of quests for love. Both narratives paradoxically suggest that love is both incompatible with and requires time: it is only from within a time-bound perspective that the dream of timelessness can appear as such. As Lamia particularly emphasizes, gods fall in love with mortals who strive to be god-like, which is what gods cannot do: there’s something wonderful about Lycius at the races appearing “like Jove” which Jove himself could never manifest. Time is the medium of narrative, a point which is especially underscored by the fact the Lycius appears god-like precisely while racing, as eminently human and temporal activity as there is. So although Lamia and the Eve of St. Agnes are romance narratives, insofar as they recount quests for unnarratable, timeless love, they are importantly also self-deconstructing narratives: they expose the formal incapacity of narrative to contain its own story. The love that would be narrated both presupposes and explodes the bounds of narrative time.

In Lamia, self-deconstruction is performed not only by the narrative upon itself but also by characters within the narrative upon themselves. Quite apart from the truth of Lamia and her god-love for Lycius’s god-likeness, we also see how the mortals Lycius, Lycius’s friends and Apollonius view Lamia. In a way that recalls Blake’s Songs, Keats shows us how mortals’ distorted views of the supernatural become self-fulfilling prophecies. By not respecting the constitutive dreaminess of the dream – that it can’t be temporally realized but only imagined as the opposite of time – Lycius and his peers variously pretend to take ownership of the divine and are consequently hollowed out like the knight in La Belle Dame and the poet of the Nightingale ode. First of all Lycius, in his all-too-human vanity, becomes dissatisfied with the divine bliss he and Lamia share ensconced in their love shack (the very paradox of temporally ‘becoming’ dissatisfied with timeless bliss underscores Lycius’s constitutive time-boundedness). Lycius must convert that bliss into social currency to win the esteem of his peers: “in thee I should rejoice / Amid the hoarse alarm of Corinth’s voice” (II, 60-1).  Likewise his friends at the banquet become intoxicated to the point that Lamia is “no more so strange,” about which Keats comments that “wine will make Elysian shades not too fair, too divine” (II, 211-2). Lycius’s vanity and his friends’ self-indulgence foreshadow and are continuous with the ultimate heresy against the “strangeness” of the divine dream (“the Elysian shade”): Apollonius’s “unweaving of the rainbow,” reducing what was a source of “awe” to one among the “dull catalog of common things.” “Lamia” is commonly read as a more or less straightforward critique of “cold philosophy” which “clips angels’ wings.” This critique is doubtless central to the poem, but we can’t let it eclipse Keats’s larger point that respecting the strangeness and awesomeness of the divine means respecting its status as a dream. So just as St. Agnes’s concluding scene of mortal decay functions to preserve the “phantom”-form of the lovers’ rapture, so too there in a sense in which by “clipping the angels’ wings” Apollonius also implicitly (and unwittingly) sets them free to fly again. He releases Lamia back to the realm of fantasy. Thus by making Lamia “melt into a shade” (II, 229-239) Apollonius despite himself arguably restores her to her properly divine place outside time.

Likewise his friends at the banquet become intoxicated to the point that Lamia is “no more so strange,” about which Keats comments that “wine will make Elysian shades not too fair, too divine” (II, 211-2). Lycius’s vanity and his friends’ self-indulgence foreshadow and are continuous with the ultimate heresy against the “strangeness” of the divine dream (“the Elysian shade”): Apollonius’s “unweaving of the rainbow,” reducing what was a source of “awe” to one among the “dull catalog of common things.” “Lamia” is commonly read as a more or less straightforward critique of “cold philosophy” which “clips angels’ wings.” This critique is doubtless central to the poem, but we can’t let it eclipse Keats’s larger point that respecting the strangeness and awesomeness of the divine means respecting its status as a dream. So just as St. Agnes’s concluding scene of mortal decay functions to preserve the “phantom”-form of the lovers’ rapture, so too there in a sense in which by “clipping the angels’ wings” Apollonius also implicitly (and unwittingly) sets them free to fly again. He releases Lamia back to the realm of fantasy. Thus by making Lamia “melt into a shade” (II, 229-239) Apollonius despite himself arguably restores her to her properly divine place outside time.

cognitive science and Jane Austen

from the ny times (nb., they refer to untagged indirect speech as ‘free indirect style,’ a fancier way of saying the same thing):

5 page essay due at exam, April 27 March 29, 2010

Like the previous 2 page essays this is an exercise in formal analysis, but this time I’m asking that you compare one work of prose and one of poetry. The two works must be by different authors; otherwise they can be any you’ve read this semester except those you’ve written on already.

So, as in the previous two assignments, your task will be to describe the formal techniques by which subjective perspectives are constructed and ironized or otherwise problematized, questioned, parodied or juxtaposed with contradictory perspectives. Here though you will be comparing how such construction works in prose with how it works in poetry. The aim of the assignment is for you to learn something about the difference between the function of prose and that of poetry, and thus to further enrich your understanding of literary form as we’ve been studying it all semester. You can certainly argue that your two chosen examples achieve similar ends; but if so you’ll have to describe the different means by which they do so.

Here’s a by no means exhaustive list of possible topics to give you a sense of the assignment: don’t feel that you either have to choose one of these examples. As always PLEASE SPEAK WITH/EMAIL ME IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS OR WANT TO DISCUSS A TOPIC

- Coleridge or Byron’s and De Quincey or Hazlitt’s approaches to juxtaposing urbane, ironic narrator’s perspectives with a more or less unspoken or unspeakable violence or sexuality underneath the social surface.

- Keats and De Quincey on emancipatory vs. oppressive consumerism

- Byron or Keats and Hazlitt on having and not having gusto.

- The self as thing in Wordsworth’s prose or Keats’s letters and Blake or Properzia Rossi or Coleridge or many others…

- Keats and Shelley (and/or Blake) on visionary imagination, dreams or “soul making” (for prose you could take either Keats’s letters or Shelley’s “Defense.” NB: a more or less straightforward theoretical essay like Shelley’s Defense or Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria doesn’t have the formal complexity – the ironic differentiation among voices or perspectives – as Hazlitt’s Fight or De Quincey’s Confessions, or prose fiction like Austen’s; so if you write on one of the theoretical essays it will a matter of interpreting its claims and applying them to the formal complexities of a poem.)

- Coleridge and De Quincey on altered consciousness.

- De Quincy and Blake or Robinson on the perspective of the urbanite.

- Austen and Byron or any number of poets on the picturesque, or on the first love vs. second love.

- Coleridge’s primary and secondary imagination and fantasy (or “negative capability”) in Shelley or Keats.

- Women’s perspectives in Austen or Wollstonecraft and Hemans or Smith.

- Disenchantment, Second Nature, Violence/Suffering/Trauma in Burke, Rousseau, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Smith.

- critique of slavery in poetry vs. prose

final exam format

The exam will be open book but closed notes. This means that notes you’ve written into your Romanticism anthology or copy of Sense and Sensibility are OK, but notes written on paper other than the pages of those two books isn’t allowed.

The exam will be divided into three approximately equally weighted parts:

1. short answer: you will be asked to define terms or describe details from the reading which I’ve discussed either in lecture or online (but probably both).

2. ID: you will be given several quotes asked to identify text each comes from and explain its function and significance in that text.

3. essay: you will choose from a selection of essay questions addressing themes and formal issues we’ve discussed in class.

Keats’s religion of consumerism March 26, 2010

It’s commonly lamented that people today take a consumerist approach to religion, that people seem to feel freer than ever to pick and choose elements of, for instance, Protestant doctrine, Jewish ritual and Buddhist discipline, in order to create an eclectic mix to fit their personal circumstances and predilections. Some see this reduction of religion to just another consumer choice as a grave indication of cultural and moral decline: if the choice of god becomes akin to the choice of car brand or dog breed, then nothing’s really sacred any more. Even taking the position that “well others may do that but i don’t” becomes dubious because even if you’re resisting consumerism you’re doing so as a matter of implicitly consumerist individual choice.

One way of looking at Keats is as responding to this defeat of the sacred by consumerism in two ways: 1) he accepts it as an inevitable fact of modernity – it’s not a matter of decline but is simply the only cultural logic we modern people know; it would be ridiculous to suggest we could approach the world otherwise than as consumers – but 2) he argues that for just this reason the equation should be inverted, and instead of thinking about how religion has been eroded by consumerism we should tease out the religious impulse, the sacredness, intrinsic to consumerism itself. Yes consumerism is a bummer; as ‘la belle dame sans merci’ and ‘nightingale’ show, buyer’s remorse can happen on a level that is completely devastating, soul-destroying. But why shouldn’t the modern consumerist era have a god of its own, a god that, as Keats puts it in the urn ode, responds to “our” specific “woe”? In other words: if the modern destruction of sacredness is a form of suffering, then why shouldn’t consumers dream of the alleviation of this specific form of suffering? This question is akin to the question with which Keats begins The Fall of Hyperion:

…Who alive can say

‘Thou art no poet; may’st not tell thy dreams?’

Since every man whose soul is not a clod

Hath visions, and would speak, if he had loved

And been well nurtured in his mother tongue (11-15)

Keats’s method of reenchantment proceeds not by attempting to reverse modern disenchantment or (a la Wordsworth) mourning it, but by taking this disenchantment to its logical conclusion in order thereby to discover/invent a new, properly consumerist form of enchantment.

Buyer’s remorse

St. Agnes, La Belle Dame Sans Merci, and the Ode to a Nightingale are implicitly poems of consumerist disappointment. They all tell a common story about the impossibility of realizing the consumerist dream of complete subjective fulfillment. Whether in the form of the sexual union of Porphyro and Madeline, the knight and the fairy, or the poet and the nightingale, each poem shows that fulfillment of the dream (if not the dream as a dream) is something incompatible with reality as we know it. No sooner does the dream seem to be realized than it turns into a “phantom”: this is the term Keats uses to describe Porphyro and Madeline as they escape the castle. The reality we’re left with at the end of this poem, as at the end of the other two poems too, is all the more miserably disenchanted for the fleeting appearance of the dream.

Yet the beadsman gives us an indication of Keats’s solution to this dilemma (the dilemma of the incompatibility of the consumerist dream and consumerist reality): for the beadsman is at home in the cold ashes of the disenchanted reality but he also manages to worship something beyond this reality. The beadsman accepting the ashes of consumerist disappointment is the precondition of his worship.

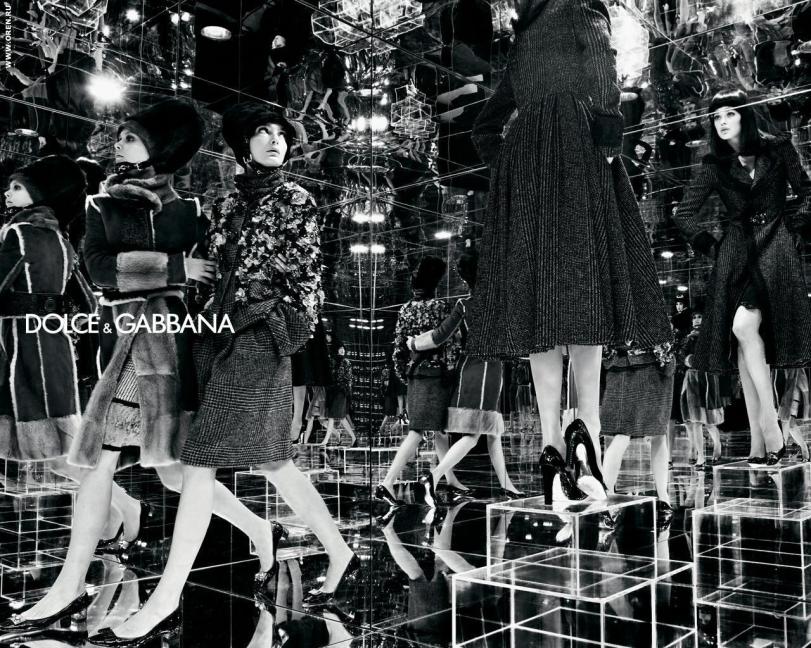

Similarly I think the ad below very provocatively suggests the deadness of its own imagery. It reminds me of the beadsman’s ashes: in this chaotically black and white hall of mirrors it’s hard to distinguish the women from their reflections although the distinction means less than it might since the women are so mannequin-like to begin with. Our gaze is captured by a woman whose own gaze is captured by another woman (or is it a mannequin? how would be know? does it matter?) whose image we also see reflected but whose unreflected body (which is actually the object most directly before us) is headless even as it seems suspended by the neck. And once we notice this morbid detail we might proceed to notice that the central woman’s eyes are rolled back in her head like a corpse’s. The ad doubtless projects images of beauty, but it also draws Keats’s ruthless line of impossibility between such images and actual life. This isn’t a beauty to be lived; it’s only place is in a fantasy that is outside of life.

Like Keats this ad uncovers the deepest lie of consumerism which is its promise precisely to release us from consumerism. The essential promise of every commodity is: buy me and you’ll be liberated from your sense of inadequacy, your need to keep buying things. So Keats subverts consumerism by forswearing the desire to escape it. The trick to experiencing consumerism in an emancipating rather than oppressive way is to quit fighting it: quit pretending that you can actually possess and live the fantasy that ads are selling and instead learn to love the fantasy in its very impossibility. There’s an echo of Shelley’s Prometheus here: just as Prometheus transcends his rivalry with Jove by forgiving him, the beadsman transcends consumerism by accepting that it turns actual life to ash. We only grasp the full beauty of the phantom-dream of porphyro’s and madeline’s rapture once we accept that it isn’t accessible in reality but only in fantasy.

Keats’s religion of consumerism = communion of fanatic dreamers

The odes to psyche, the urn, melancholy and autumn are all attempts to perform a certain kind of worship; and it would not be wrong to think of the worshiper/poet in each of these cases as a version of the beadsman from st. agnes. In each case experiencing a disappointment and/or marginalization akin to the beadsman’s is the precondition of proper worship. But this resignation to personal disappointment is also shown to prepare the poet to participate in a kind of fantasy that transcends individuality and even time. This always involves imagining something impossible – hearing inaudible music (urn), building a church for a goddess without worshipers (psyche) – and turning pain into pleasure (melancholy) and making time stop (autumn). All of these exercises in impossibility can be seen as forms of spiritual discipline: helping us learn to resign ourselves to personal disappointment in order to appreciate the fantasy of an object (like the urn) beyond possession. This is what Keats would teach the lovers forever about to kiss on the urn: to enjoy the fantasy as a fantasy; not as a blueprint to be realized, a means to an end, but as an end in itself: fantasy for its own sake. But doing this requires the beadsman’s resignation to the ashes, forswearing attempts to actually sensually realize and personally possess the fantasy. The point of this resignation is that it acknowledges in advance the futility of all such attempts. For us the fantasy is there to be worshiped in its very otherworldliness, not to be realized and owned.

Hence in the Fall of Hyperion Keats constructs a goddess precisely of failed poets—of those whose fate it is to be categorized as fanatic dreamers as opposed to legitimate poets. This is Moneta; but Moneta doesn’t promise to redeem these lost souls in any normative way; rather she appears more like a symptom of the un-redeemed, disenchanted condition of modernity per se, its inherent disposition to impotent fanatasism. Moneta’s name means money, her brain is hollow, and her eyes are gazeless and glassy. Moneta exemplifies the commodity fetish. If modernity conduces not to legitimate art but to consumerist fanaticism, then Keats reasons that for precisely this reason fantasism provides the basis for a new kind of art: art as a kind of consumerist worship. Keats correlates Moneta’s objectification with her non-exclusivity. Like Warhol’s Marilyn she lives only in the imagination of her admirers, but this imaginary life depends upon her actual deadness: her thing-like status, what makes her brain hollow and her eyes “blank,” is also what allows her to “beam splendid comfort” to the multitudes:

Hence in the Fall of Hyperion Keats constructs a goddess precisely of failed poets—of those whose fate it is to be categorized as fanatic dreamers as opposed to legitimate poets. This is Moneta; but Moneta doesn’t promise to redeem these lost souls in any normative way; rather she appears more like a symptom of the un-redeemed, disenchanted condition of modernity per se, its inherent disposition to impotent fanatasism. Moneta’s name means money, her brain is hollow, and her eyes are gazeless and glassy. Moneta exemplifies the commodity fetish. If modernity conduces not to legitimate art but to consumerist fanaticism, then Keats reasons that for precisely this reason fantasism provides the basis for a new kind of art: art as a kind of consumerist worship. Keats correlates Moneta’s objectification with her non-exclusivity. Like Warhol’s Marilyn she lives only in the imagination of her admirers, but this imaginary life depends upon her actual deadness: her thing-like status, what makes her brain hollow and her eyes “blank,” is also what allows her to “beam splendid comfort” to the multitudes:

[her eyes] seem’d visionless entire of all external things; they saw me not

But in blank splendour beam’d like the mild moon

Who comforts those she sees not,

who knows not what eyes are upward cast.

Whatever “comfort” Moneta offers is predicated upon a painful tearing apart and reconstituting of the subject who feels it: it’s a scary, somewhat dehumanizing insight to realize how much of our identity is invested in the commodities we consume. But for Keats the way to re-humanizing, to re-gaining self-possession, is precisely to quit denying this investment, to take ownership of our consumer fantasies as such: again Keats’s point is that we can transcend consumerism only by utterly surrendering to it.

Sample Fanatic Dream #1: Transcending Individuality

This clip from the movie “Bottle Rocket” is recommended mostly by how funny it is but I think it also illustrates the social appeal of a fanatic dream contrasted with the oppressive, normative (i.e. the opposite of fanatic) coolness of the guy in the bronco. Like the beadsman or the addressee of the ode to melancholy, the Luke Wilson character embraces disappointment; he says “goddamn it” because he knows this plan is going nowhere. In exchange though, like the lovers on the urn, he can appreciate the dream for its own sake, just for the sake of its dreaminess. He gives up the need to possess values like coolness in order to sustain a dream. But like the ode on the urn the movie suggests there’s something way richer and more intimate about this dream than about actually being cool (which in contrast seems rather dull and mean): richer because we get closer to the point of our ideals of coolness, love, beauty, etc. by just dreaming about them than by claiming to realize and possess them, and more intimate because a kind of mind-meld is possible in the dream (like the merging of the odors of the flowers in st. agnes); we become indistinguishable co-authors of the dreams we share whereas claims to realize and possess our dreams cut us off from one another.

Fanatic Dream Samples #2 & 3: Transcending Time

This brilliant animated video is about a flightless kiwi bird’s dream of flying. So the premise shares the Keatsian form of bridging unbridgeable gaps, imagining the impossible (e.g., hearing the inaudible, etc.). It’s striking how the short video is able to register different orders of time: it begins in the normal time of the lived present, but with the shot down the cliff we’re made conscious of how the present extends far back into history: the bird’s been nailing trees like this for years! Knowing that this effort extends back for years becomes significant once the bird jumps and we realize what the purpose of all this work has been: constructing the illusion of flying. The video wonderfully draws us into this illusion by turning the camera so that the vertical fall appears as horizontal flight. The effect of this maneuver is that it, like the ode on the urn, makes us see what we know is not there. It crystallizes the fantasy of flight as a fantasy: we’re inside the bird’s head, living his dream along with him/her. The crucial point of Keats’s ode on the urn is that from this perspective the normal time of the living present and the temporal transcendence of the dream become indistinguishable: insofar as we’re inside that fantasy of flight–the fantasy that existed only in the bird’s head for all those years of tree nailing–we’re outside of time. In exactly the same way the urn’s unheard melodies confront us today exactly as they had confronted ancient Romans: to attune ourselves to that inaudibility is to participate in the same experience that they had, and hence to step somewhat out of time. Thus although this video ends sadly, insofar as time itself is transcended this sadness is transcended as well.

Similarly at the start of the movie “Before Sunset” Ethan Hawke describes how love can get encapsulated in a pop song that (like the urn and, especially, the experience of re-hearing an “old melody” Keats discusses in a letter [1350]) reveals “time is a lie.”

Keats’s letters III

1. What does this sentence mean: “men of genius are great as certain ethereal chemicals operating on the mass of neutral intellect – but they have not any individuality, any determined character” (1349)? It certainly anticipates Keats’s later claim that “the poet is the most unpoetic thing;” but what does the chemical simile add to this claim? is it not somewhat (rather Byronically) reductive to speak of genius so materialistically?

2. What’s the meaning of Keats’s comparison of the imagination to Adam’s dream (1349-1350)? He illustrates his point by describing how re-hearing a melody can revive sensations experienced when it was initially heard, but he adds that in the interim these sensations are “heightened,” improved, by the imagination even to an impossible degree, so that for instance “the singer’s face [seems] more beautiful than it was possible, and yet with the elevation of the moment you did not think so.” Is Keats right that we idealize memories, or is he just being a sanguine romantic? what’s at stake in this question? does it relate to Hazlitt’s account of gusto?

3. What’s the rationale behind Keats’s claim that “the excellence of every art is its intensity” (1350)?

4. Finally the ultimate Keatsian question: what does “negative capability” (1351) mean? Try to tease out the logic behind Keats’s examples and counter-examples: Shakespeare had it, Coleridge didn’t; it’s a matter of being “content with half-knowledge, uncertainies, mysteries, doubts” rather than “irritably reaching after fact and reason;” it is a “sense of beauty” that “obliterates all consideration.”

Paradise Lost, Book 8, ll. 452-490:

Hee ended, or I heard no more, for now

My earthly by his Heav’nly overpowerd,

Which it had long stood under, streind to the highth

In that celestial Colloquie sublime, [ 455 ]

As with an object that excels the sense,

Dazl’d and spent, sunk down, and sought repair

Of sleep, which instantly fell on me, call’d

By Nature as in aide, and clos’d mine eyes.

Mine eyes he clos’d, but op’n left the Cell [ 460 ]

Of Fancie my internal sight, by which

Abstract as in a transe methought I saw,

Though sleeping, where I lay, and saw the shape

Still glorious before whom awake I stood;

Who stooping op’nd my left side, and took [ 465 ]

From thence a Rib, with cordial spirits warme,

And Life-blood streaming fresh; wide was the wound,

But suddenly with flesh fill’d up and heal’d:

The Rib he formd and fashond with his hands;

Under his forming hands a Creature grew, [ 470 ]

Manlike, but different sex, so lovly faire,

That what seemd fair in all the World, seemd now

Mean, or in her summ’d up, in her containd

And in her looks, which from that time infus’d

Sweetness into my heart, unfelt before, [ 475 ]

And into all things from her Aire inspir’d

The spirit of love and amorous delight.

Shee disappeerd, and left me dark, I wak’d

To find her, or for ever to deplore

Her loss, and other pleasures all abjure: [ 480 ]

When out of hope, behold her, not farr off,

Such as I saw her in my dream, adornd

With what all Earth or Heaven could bestow

To make her amiable: On she came,

Led by her Heav’nly Maker, though unseen, [ 485 ]

And guided by his voice, nor uninformd

Of nuptial Sanctitie and marriage Rites:

Grace was in all her steps, Heav’n in her Eye,

In every gesture dignitie and love.

I overjoyd could not forbear aloud. [ 490 ]

Keats’s odes March 24, 2010

Odes are traditionally addresses to the gods of some kind, sung in praise, supplication and/or beseeching. Keats’s odes are addressed to an electic set of god-like things. The order in which they were written in a matter of some controversy but according to one arrangement the odes are addressed:

1. [To a mood (indolence) (which we’re not reading)]

2. To a goddess (psyche)

3. To a nightingale

4. To an urn

5. To an emotion (melancholy)

6. To a season (autumn)

In his letter on the “Vale of Soul-Making” Keats argues that salvation requires “the medium of a world like this;” in other words, the soul isn’t otherworldly but strictly a function of worldly existence. A great way to think about Keats’s odes is as worldly media of soul making: aesthetic experiences through which something like soul gets generated. The most tangibly worldly of the entities to which Keats’s odes are addressed are the nightingale and the urn, whereas the one that is most recognizably ode-like and concerned with salvation is the Ode to Psyche. So good general question to ask is what do the odes to psyche, nightingale and Grecian urn do differently? All present an image of immortality in one way or another; but do the various images of immortality have different implications?

Psyche

In light of Keats’s critique of Christianity in his letter on soul-making, is his talk of worship in Psyche to be taken literally? is he proposing a kind of religious practice here? what could it mean to worship in a church of the mind? wouldn’t this be at odds with Keats’s insistence that the soul is rather worldly rather just spiritual?

A large section of this poem is repeated; what is the significance and function of this repetition? does this give it a ritualistic form?

Nightingale & Urn

In nightingale the sense of sight is sacrificed to that of hearing, just as in the urn the sense of hearing is sacrificed to that of sight. So a crucial two-part question to ask in these poems is: 1) what’s the specific way in which sounds and sights respectively ‘speak’ to us? what does one ‘say’ better/worse than the other? what is at stake in each particular mode of aesthetic reception? what are the respective connotations of visual and auditory images? and 2) how is Keats playing these connotations off of one another? does he finally value them more for what they can or for what they can’t ‘say’?

In nightingale the sense of sight is sacrificed to that of hearing, just as in the urn the sense of hearing is sacrificed to that of sight. So a crucial two-part question to ask in these poems is: 1) what’s the specific way in which sounds and sights respectively ‘speak’ to us? what does one ‘say’ better/worse than the other? what is at stake in each particular mode of aesthetic reception? what are the respective connotations of visual and auditory images? and 2) how is Keats playing these connotations off of one another? does he finally value them more for what they can or for what they can’t ‘say’?